- Home

- James McNaughton

New Hokkaido Page 2

New Hokkaido Read online

Page 2

‘I have an ashtray,’ Marty says, lighting up. He’s holding a full beer bottle and an empty bottle for ash, and smoking at the same time.

Chris grins at his juggling routine. ‘Good to see you, bro. Good to get out. Jesus.’

‘Yeah man, it’s like you’ve been under arrest. Should be a good night, eh? Seen anything you like the look of yet?’

A belligerent voice. ‘Too formal, mate. Japs dress up for parties. Kiwis go casual.’

Chris guesses the man who has planted himself next to him, clad in a bush shirt, jeans and gumboots, is a prop. Yet even he has flouncy hair browned with dye. He sticks his hand out and they shake as Marty makes introductions. His name is Stew and he’s just moved down from Taranaki to play rugby. Marty explains that Chris can’t play this year because of his job. Stew says he’s heard about him, the missing lock, and it’s a damn shame.

The two girls who came in behind Chris enter the lounge, glowing and bright-eyed from their walk in the night air, surprisingly tall in their high heels, which he likes, but their long loose dresses and old cardigans look odd. He can see they’ve powdered their noses since arriving, but their big hair has been somewhat naturalised by the weather, a good thing in his opinion. They smile and join the group, shake hands and exchange names. He likes the look of Emily, a busty brunette with brown skin and a bright smile. Neither she nor her friend has the affected inward-pointing toes and helium voices of J-Pop idols that an increasing number of young Kiwi women are adopting.

The prop taps the ash from his cigarette into Marty’s bottle. ‘Good man,’ he tells him.

The girls smile and Chris offers his packet of expensive Silk Cut. They both accept and soon they’re tapping ash into the bottle Marty gallantly wields.

‘Your dress is a little formal,’ Emily notes, with a twinkle in her eye.

He wants to tell her he has money, prospects, a life. ‘I came straight from work.’

‘What do you do?’ She’s interested; they all are, even the thick-necked prop, Stew.

‘English teacher.’

‘Where?’

He translates the Japanese name: ‘The Language Academy.’ Met with blank looks, he adds, ‘It’s north of the intersection of Teramachi and Oshikoji Streets.’

‘He means on Willis Street,’ says Stew, and Chris is embarrassed to have used the official Japanese address system. ‘Jeez, I know that,’ Stew continues, pressing home his advantage in front of the women, ‘and I’m from Taranaki.’

Thankfully, the women don’t laugh.

‘How’d you get that job, mate?’ asks Stew. The question is aggressive, as if Chris has done something unsavoury to get it, something unpatriotic.

‘I got a high score on the test.’

‘What test, mate?’

‘An open test at the Academy. A public test. Anyone could walk in and take it.’

‘I didn’t hear about that,’ says Emily. ‘I’ve been looking for work for ages.’

He feels he must be completely honest with her, particularly at this early stage in their relationship. ‘Well, it was a Japanese test. You have to be good at Japanese to teach English. That’s the main requirement.’

‘That’s fucked up, mate. Why are you so good at Jap?’

Ignoring the prop, Chris lights another cigarette. Obviously, he thinks, because I’m good at it. He knows Emily will understand.

‘Why are you so good at Jap?’ repeats the prop.

‘It’s compulsory. I picked it up.’

The prop waves his hand before his face. ‘Shit, mate, how do you smoke those things?’

Silk Cut are only 75% tobacco. ‘For good health,’ he replies.

‘It’s like smoking lawn clippings,’ says Stew, wrinkling his nose.

‘I wouldn’t know,’ Chris says, without smiling. ‘I’m not from Taranaki.’

Stew doesn’t smile either. He drops his butt in Marty’s bottle, produces a packet of Hillary, lights up, and blows smoke in Chris’s direction.

The girls have spotted someone across the room they know and wave with their fingers in greeting. Obviously relieved to escape the growing unpleasantness between Chris and Stew, they go to see their friend. It seems to Chris that the sun has gone behind a cloud. And the prop is still in his face.

‘You don’t just pick up Japanese like a suitcase, mate. You have to work at it.’

Chris decides he likes Stew’s forthrightness. Honesty is a valuable trait. He’s right, his line of questioning is actually reasonable, and he will tell Stew the truth: that he is the famous Patrick Ipswitch’s younger brother and was exposed to a different environment from most kids. It’s a good story, he knows, and he’s about to launch into it when a wiry elderly man standing at the head of the flagged trestle table calls for quiet.

Conversation stops and the knots of people in conversation open up and turn to the speaker. Maybe twenty people, a thrilling number in a private house, now encircle the table. The steely little man is neatly dressed in a polo shirt, pleated trousers and hard shoes. His hair, although entirely grey, is thick and swept to the side.

‘My name’s Brian Murray,’ he says in a strong, clear voice. ‘John invited me here as a kind of “cultural consultant”, I think he called it. He’s been kind enough to host this event and I think we should thank him for it.’

The host, a gingery man of thirty-five in a vintage corduroy jacket, woollen suit trousers and black dress shoes like Brian’s, raises a hand and smiles to a ripple of applause.

‘Let me tell you a little bit about myself,’ continues Brian. ‘I was an artillery gunner in the war. I fought in Burma and was lucky to get out. Back in New Zealand I manned the guns at Makara and am proud to have helped sink the heavy cruiser Maya.’ Everyone applauds, someone whistles. Brian’s face falls. ‘I had fifteen years hard labour in Featherston after that and saw most of my friends die. Mainly from illness and starvation, but some were beheaded.’

As Brian speaks of the atrocities in the camps, the younger people glance around the room at one another. Chris is the tallest and the only male not dressed as a farmer. Judging by Brian’s smart attire, it appears to him that the Kiwi dress around him is not authentic. Everyone looks like low-paid labourers, which is exactly what they are now under Japanese rule. Why not dress as managers, as people who own their own land and control their own destiny? And surely, he thinks, we used to leave our gumboots outside rather than traipse sheep shit through the house. Emily’s outfit, with its ancient heavy cardigan, is disappointing. Her big bust and long neck would look spectacular in a little black dress. She should wear jewellery, put her hair up. The effect would be stunning. She flicks her eyes at him and he smiles warmly, confident of his feelings for her. After a very brief shy smile in return, she concentrates on Brian, who is rounding up his POW experiences.

‘I know you’ve all heard stories like this before,’ he says sadly, ‘and I don’t want to spoil the party. It should be a celebration. A celebration of who we are, not what those bastards tell us we are.’ The applause is strong. ‘John, your kind and courageous host, asked me to duplicate a genuine Kiwi party. Well, this is what we used to do forty-odd years ago when we were free. Before we became tenants in our own country. The food’s out, as you can see, and there’s not a single bloody raw fish in sight. Thank you, ladies, for bringing a plate. Of course in our day you wouldn’t have to drop it around in secret a day or two beforehand, so extra credit must go where extra credit’s due. Let’s hear it for the ladies.’ Chris contributes energetically to the round of applause, which the women instinctively acknowledge with a bow.

‘No bowing!’ The gleeful cry is of someone catching out a mate in a drinking game. Heads turn to the red-faced man who has been on door duty.

‘Good Kiwi food,’ says Brian, and everyone turns back to him. ‘It’s all cooked!’ He pauses for more applause, which comes less certainly. ‘I don’t know about this sitting on the floor business they make us do we when we go out. It se

ems another way of keeping us down.’ He senses he’s losing the room. ‘What was natural to us was that the men would relax in the kitchen standing up and the women in the lounge, sitting down with a cup of tea.’ Sensing disapproval, he adds, ‘Or some vodka and lemonade. Then, after a couple of drinks and a nibble we’d have a little dance to the gramophone. Please enjoy yourselves. You’ll make your ancestors proud.’

Brian is applauded warmly, but his remark about separating the sexes into kitchen and lounge is not what Chris wanted to hear. He tries to catch Emily’s eye on the way to the kitchen but she’s busy talking to her friend. Someone behind him says, ‘Nice suit, mate,’ as the men crowd into the kitchen, gumboots clomping.

‘Better access to the piss, lads,’ says a tall, thin, pale-faced boyish man with a yellow-and-brown mullet. ‘Our ancestors knew what they were doing.’ His bush shirt is too big, like a dress on him, and his thin white legs disappear into oversize gumboots with a hole in the toe. Yet his voice is surprisingly deep.

While Chris is getting a beer from the fridge, someone else says, ‘Nice suit.’ He turns to see the hard faces of twelve men in a circle, bulky in their woollen bush shirts. The comment could have come from any of them.

The circle parts for Brian, who raises his bottle. ‘More men in the kitchen than allowed in a house.’

‘Hear, hear.’

‘Sweet.’

They all touch bottles, a circle of men reaching into the centre. It’s unusual, different from the strictly monitored rugby team meetings in the clubhouse, and electrifying, a situation full of possibilities both exciting and terrifying. Despite his nervousness, Chris nods his gratitude to Marty for inviting him. He wants to share the news about Paris he heard in the staffroom but knows he must wait for Brian to speak again. The older man looks thoughtful and tired at close range, a lucky survivor, as if speaking about the death camp has released distressing memories and drained him. But he has made it, somehow, and has wisdom to share. He appears to stare at something in another dimension, something vivid but hard to make sense of. The silence becomes awkward and Chris is about to speak when Brian’s eyes focus and come to life. He blinks slowly and nods his head.

‘Auckland tomorrow. Should be a good game.’

‘We’ll need to close Kirwan down.’

‘Yep.’

‘He won’t get the ball, mate. We’ll starve them of possession.’

Chris is deeply disappointed. As the conversation stutters around him, lurching from injuries to the weather report to Gallagher’s form with the boot, he wonders if their conversation would be more fluid and abstract in Japanese. Maybe our English is rustier than we realise, he thinks.

When the conversation falters, Brian says, ‘I’d better check on the ladies.’

‘When do we get to check on them?’ asks Chris, when he’s safely out of earshot.

‘After we’ve sunk some more piss,’ says the prop.

‘Reckon,’ says another man. ‘I’ll need a few before the dance.’

‘I’ve never done that kind of thing before.’

‘Dancing?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I did once, but not in gumboots.’

‘Ha ha ha.’

‘I went to take mine off at the door and got yelled at.’

‘Same, bro.’

‘So, this dancing thing—’

‘The only fuckin’ thing the Japs taught me was to bow and shuffle.’

‘Yellow fucking scum.’

After a round of abuse, to which Chris does not contribute, there comes a silence. The dance still looms.

‘J-Popsters do Western dancing now.’

‘Don’t watch that shit.’

‘Fuck, mate.’

‘I saw it on a screen downtown. I couldn’t help seeing it.’

‘Just bounce on the spot,’ Marty says, ‘and look happy.’

‘I could murder one of those sausage rolls.’

‘Me too, bro.’

‘I think the ladies go first.’

‘They’ll eat the fucking lot if we’re not careful.’

A man leaves the circle and peers into the lounge. ‘It’s all right, mate,’ he reports upon his return, ‘hardly touching them. Don’t like your chances of getting any pavlova, though.’

‘That’d be right.’

A general laugh ensues and Chris sees the hard faces around him relax properly for the first time. Yet he has the feeling no one is quite sure why they’re laughing.

‘Round two,’ announces the tall thin man in his oddly deep voice as he opens the fridge. ‘To a free New Zealand,’ is the toast, and the bottoms of the bottles go up. Glug, glug, glug. As the third round is taken from the fridge and distributed, the man says to Chris, ‘What’s with the suit?’

Clearly everyone wants to know. Chris tells them he came straight from work and answers the same line of questioning the prop asked. Suspicious eyes are on him. Their faces are reddening from heat, from wearing bush shirts indoors, and from beer. Wanting to puncture their disapproval, he tells them what he heard in the staffroom, but changes the speaker from a teacher to the principal for heightened effect. It doesn’t help. They don’t care about Paris. They don’t trust him and have the right to beat him up. In fact, they’re obliged to. He looks to Marty, his friend.

‘Nervous Japs in the staffroom?’ says Marty. ‘Must be bad. Must be terrible, in fact. Excellent news.’

No one says anything. They look at Chris as if he’s a spy. He realises that he was right about the aura of violence he sensed upon arrival, but he’d never imagined it would take the form of a beating at the hands of his countrymen.

‘Paris is a long way from here, mate,’ Stew tells him. ‘Te Urewera is what you should be thinking about.’

‘True, mate. True.’

He means the Maori guerrillas in the mountainous bush in the east of the North Island, the only territory in New Zealand not controlled by the Empire. Though possibly not for much longer, Chris thinks. The Imperial Japanese Army has launched a major offensive with helicopters, rockets and thermal-imaging devices fresh from Russia. The guerrillas have small arms and homemade bombs, and starvation and disease.

‘They’re just fighting for survival,’ he says.

‘Fuck you, man.’ It’s the boy with the deep voice.

Someone steps back and pulls his bush shirt off over his head. Standing in a black singlet, flexing mighty biceps, he stares at Chris. A couple more follow his lead. They’re dressed the same. The black singlets are a declaration of war; they are ready to fight.

‘We need outside help,’ Chris says mildly, although his heart gallops and breath comes quickly. ‘Looks like we’re getting some in Europe.’

‘We need both, man,’ says the deep-voiced boy, whose bone-thin legs indicate why he’s left his bush shirt on. ‘Inside and outside. What’s your name anyway?’

‘Chris Ipswitch.’

Using Japanese pronunciation, the boy says, ‘Ip-u-sa-wit-ich-u?’

‘My bro.’

‘The sumo champ?’

‘Yep.’

‘Get the fuck out of here!’

‘Into the lounge?’ With the ladies, he means: a failed attempt at humour.

Several voices are raised at once, and a surge of grudging respect comes his way. They look at him again, recalibrating his suit and fancy job. But the deep voice wins out. ‘Your bro shacked up with a Jap and had her bastard baby.’

‘Sarah’s my niece. She’s a great kid.’

Brian’s back with the host, the gingery man in vintage corduroy who has been with the ladies all along. It’s a privilege Chris is willing to concede, given the risk he’s taking. ‘Whoa, whoa,’ says the host, flapping his arms, ‘keep it down, boys. We have to watch the noise.’

‘Yeah, but Mr Suit here is Ip-u-sa-wit-ich-u’s little brother.’

Brian looks pained. ‘Look, let’s all be friends. Come and have a sausage roll.’

‘He works at the Langu

age Academy, too,’ offers the prop. ‘Bet he’s a green.’

It’s true; Chris does have a green ID card, indicating his high level of trustworthiness. It came with his job and he wonders what to say.

‘He’s cool,’ says Marty, sparing him the need to reply. ‘I invited him. I’ve known him for years. Damn fine lock.’

Brian processes this. ‘Do you have contact with your brother?’

‘Yeah. I love the guy.’

The boy with the deep voice and skinny white legs appeals to Brian. ‘He shacked up with that Jap bitch and had a half-breed with her.’

Chris remains calm. ‘That half-breed’s my niece. My brother was an athlete. He was the best. Everyone loved him when he was beating the Japs. Remember? He was a national hero. Suddenly he’s gone from hero to zero just because he fell in love with a woman. She doesn’t care about the Empire. She just wants to raise a family.’

Red-faced from beer and his bush shirt, a young man who hasn’t spoken before says with great intensity: ‘He’s disgraced our glorious dead.’

‘Shame.’

‘True.’

Chris’s heart sinks. The kitchen is against him. The black singlets are ready to pounce. It seems the only thing preventing them from beating him up is the noise it will make.

‘C’mon,’ says Marty, ‘Chris is solid.’ His opinion carries enough weight to defer violence for a moment.

‘I love my bro,’ says Chris. ‘I’ll leave.’

‘No, don’t do that,’ says Brian. ‘We’re not sending you out like this.’

Chris becomes aware of rain lashing the roof and kitchen window.

‘You fellows join the ladies in the lounge. Now, don’t just stand around the food table and talk about rugby. Pick one item and take it with you when you make conversation with a lady. It’s up to you to ask them to dance—don’t let them down. I’ll have a word to Chris here in private.’

No one moves a muscle so Brian leads him away, moving quickly and fluidly down the hall. He turns into a bedroom and Chris pauses, fearing a trap. Yet he follows anyway, into the musty dark, where he expects the steely little man will try to kill him. Brian snaps on a light and closes the door.

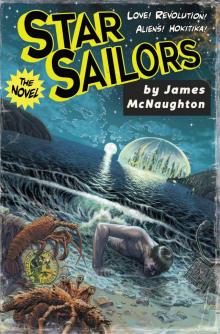

Star Sailors

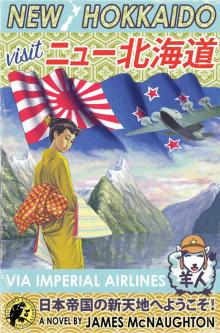

Star Sailors New Hokkaido

New Hokkaido